Back in February I wrote about the huge part Ian Richardson played in my life (see Old and desolate). On Tuesday, three months after his death, a memorial service was held at the Actors’ Church – St Paul’s Covent Garden. My partner and I were lucky to be able to attend it. Here you will find a lovely account of what it was like, by the writer Brian Sibley, and here a complete list of all the famous theatre/film/TV folk who came to pay tribute to their late colleague .

What these articles don't mention is that Helen Mirren started crying even before the service began and could hardly be heard when she read out the moving ‘Dirge Without Music’ by Edna St Vincent Millay. It was very endearing.

What they don't tell you either is that we all came out of the church to be met by a swarm of paparazzi, professional autograph hunters and pushy elderly fans of both sexes. What is wrong with these people? Have they no shame?! OK, there had been laughter as well as tears during the service, but this was still a sad occasion. Who turns up at such an event and behaves as if it were a press night? I always thought that celebrities were fair game, that if you spent your life courting publicity you couldn’t complain if your privacy was invaded. I have changed my mind.

We were chatting with the actor Michael Pennington (whom I’ve known for 30 years) when a man sidled up to him, opened a folder and asked him to sign photos of himself. Michael, who’s the gentlest of souls, signed photo after photo – five or six, I think – with good grace. We were indignant on his behalf. When I said, ‘How much will these fetch on eBay?’, the guy pretended they were for a friend of his in New Zealand!

Most of the famous folk let themselves be photographed too: the last thing anyone wants is to be splashed all over the tabloids and being described as unhelpful and rude to ‘the great British public’. It was painful to watch.

After saying hello to a few more people and being stared at a lot (‘Are they famous, do you think?’ ‘Nah, don’t bother with them!’), we walked away and wandered around Covent Garden. About an hour later, we went in search of somewhere to eat. We ended up in Catherine Street and walking past one of the restaurants we noticed a couple of the autograph hunters who’d been at the church earlier, standing outside in the cold, apparently waiting for something, or someone. Obviously, a few of the ‘celebrities’ were having lunch there. They were going to be accosted and pestered again when they came out.

Slap!

Saturday, 19 May 2007

Sunday, 6 May 2007

Small pleasures from small favours

Since I’ve already denied women the right to make fools of themselves by taking up pole dancing as exercise and learning it at public classes, and thereby contributing to the backlash against feminism, I thought I would now deny women the right to have children at an age when they should be playing with their children’s children or enjoying retirement. But too much has been said about that 63-year-old mother-to-be and the subject has gone stale on me.

Instead, I want to slap people who, having acquired a little bit of power, suddenly take themselves seriously and refuse to do other people small favours, when it’s no skin off their noses.

My partner and I went to Stratford-upon-Avon for Shakespeare’s Birthday (April 23rd, in case you’ve forgotten when it was): the Royal Shakespeare Company had planned masses of events and we thought it would be good fun.

We hadn’t booked for anything (we’d learned about it too late), but we managed to attend two very interesting events (one about playing Cleopatra – with Harriet Walter and Janet Suzman; the other about the Sonnets – with Patrick Stewart and my beloved John Barton). There had been a few tickets left for the first talk, but the second one was booked up. Nevertheless we thought there might be some returns so we queued anyway. There weren’t, but just before the start we were let in, together with four or five other people, because there was space and because they took pity on us. We stood, or sat on the floor, at the back of the room, and spent a wonderful, stimulating two hours.

There was one more event we ‘didn’t mind’ attending: an interview with Judi Dench. It was to take place in the big marquee that had been erected in one of the theatre gardens (and where we’d heard the two Cleopatras earlier that day). For this too tickets were unnumbered and the queue to go in was unbelievable: it went round and round and round… We, and a very small group of other unfortunate, ticket-less people, waited for everyone to be seated. We had money in our hands; there was plenty of standing room on the side of the seating area and there didn’t seem to be any reason why we couldn’t be let in. That’s when I noticed her – Bronwyn Robertson, the most officious woman ever, and I more or less knew we were waiting in vain.

She could have said to us, “You’ve been waiting so patiently; there’s only a few of you; this is the last event of the day; I cannot deprive you of the pleasure of listening to Dame Judi, who’s come specially today – a Sunday – to give this interview. Please come in!” But she didn’t say it and everyone wandered off (one person was in a wheelchair – you’d think she would have allowed them in), disappointed. We did hear the interview for a while, because we discovered that, if we positioned ourselves in a special spot, behind the marquee, and listened closely, we could hear every word. Unfortunately, the questions were so lame and banal and so unworthy of her talent that we gave up halfway through. But that's not the point.

It would have been so easy for Bronwyn to make us all happy. But, no, it was in her power to deny us and she did. I wonder if she got any satisfaction out of it.

I first met Bronwyn in 1974, when I lived in Stratford and needed a job. She was secretary to one of the directors; she was obstructive and annoying. She was then put in charge of something or other and she carried on being unhelpful. I must have been introduced to her a dozen times. She always forgot who I was. It requires a special kind of person to ‘forget’ completely someone they see practically every day.

While I’m slapping people who deserved it in the past but who only got the utmost courtesy from me because I was still hoping to have a career with the RSC at the time I might as well mention Diana Minchall. We met in 1977, when we were both attending the Summer School and were staying in the same B&B. She knew no one; I knew everyone. By the time she went back to London she knew everyone too. Two years later, when she got a job with the RSC (in the Publicity Department), she had a head start. I had told her about the vacancy so she could apply for it and when she got the job she promised to return the favour. Yeah right!

Not only did she not help me in any way but, within a few weeks of her taking up her new post, one might have thought she was the RSC’s Artistic Director, judging from the way she started behaving. I stopped being in the secret of the gods because my contacts assumed she was giving me lots of info and I didn’t need to be told anything.

She was there for about ten years and I never got another chance to get a job with the RSC. Instead of being a help she was an obstruction. I’ve been wanting to slap her smug face for a very long time. There!

When I used to work at Penhaligon’s I had access to perfumes that everyone valued immensely. I was in a position to give my friends a few samples from time to time. And why not? My mistake is that I’ve always expected others to derive as much pleasure from doing (or returning) favours as I have.

I’m sure Judi Dench would have been very sad to know that half a dozen people were turned away that day – for no good reason whatsoever – because of some self-important official.

Slap!

Instead, I want to slap people who, having acquired a little bit of power, suddenly take themselves seriously and refuse to do other people small favours, when it’s no skin off their noses.

My partner and I went to Stratford-upon-Avon for Shakespeare’s Birthday (April 23rd, in case you’ve forgotten when it was): the Royal Shakespeare Company had planned masses of events and we thought it would be good fun.

We hadn’t booked for anything (we’d learned about it too late), but we managed to attend two very interesting events (one about playing Cleopatra – with Harriet Walter and Janet Suzman; the other about the Sonnets – with Patrick Stewart and my beloved John Barton). There had been a few tickets left for the first talk, but the second one was booked up. Nevertheless we thought there might be some returns so we queued anyway. There weren’t, but just before the start we were let in, together with four or five other people, because there was space and because they took pity on us. We stood, or sat on the floor, at the back of the room, and spent a wonderful, stimulating two hours.

There was one more event we ‘didn’t mind’ attending: an interview with Judi Dench. It was to take place in the big marquee that had been erected in one of the theatre gardens (and where we’d heard the two Cleopatras earlier that day). For this too tickets were unnumbered and the queue to go in was unbelievable: it went round and round and round… We, and a very small group of other unfortunate, ticket-less people, waited for everyone to be seated. We had money in our hands; there was plenty of standing room on the side of the seating area and there didn’t seem to be any reason why we couldn’t be let in. That’s when I noticed her – Bronwyn Robertson, the most officious woman ever, and I more or less knew we were waiting in vain.

She could have said to us, “You’ve been waiting so patiently; there’s only a few of you; this is the last event of the day; I cannot deprive you of the pleasure of listening to Dame Judi, who’s come specially today – a Sunday – to give this interview. Please come in!” But she didn’t say it and everyone wandered off (one person was in a wheelchair – you’d think she would have allowed them in), disappointed. We did hear the interview for a while, because we discovered that, if we positioned ourselves in a special spot, behind the marquee, and listened closely, we could hear every word. Unfortunately, the questions were so lame and banal and so unworthy of her talent that we gave up halfway through. But that's not the point.

It would have been so easy for Bronwyn to make us all happy. But, no, it was in her power to deny us and she did. I wonder if she got any satisfaction out of it.

I first met Bronwyn in 1974, when I lived in Stratford and needed a job. She was secretary to one of the directors; she was obstructive and annoying. She was then put in charge of something or other and she carried on being unhelpful. I must have been introduced to her a dozen times. She always forgot who I was. It requires a special kind of person to ‘forget’ completely someone they see practically every day.

While I’m slapping people who deserved it in the past but who only got the utmost courtesy from me because I was still hoping to have a career with the RSC at the time I might as well mention Diana Minchall. We met in 1977, when we were both attending the Summer School and were staying in the same B&B. She knew no one; I knew everyone. By the time she went back to London she knew everyone too. Two years later, when she got a job with the RSC (in the Publicity Department), she had a head start. I had told her about the vacancy so she could apply for it and when she got the job she promised to return the favour. Yeah right!

Not only did she not help me in any way but, within a few weeks of her taking up her new post, one might have thought she was the RSC’s Artistic Director, judging from the way she started behaving. I stopped being in the secret of the gods because my contacts assumed she was giving me lots of info and I didn’t need to be told anything.

She was there for about ten years and I never got another chance to get a job with the RSC. Instead of being a help she was an obstruction. I’ve been wanting to slap her smug face for a very long time. There!

When I used to work at Penhaligon’s I had access to perfumes that everyone valued immensely. I was in a position to give my friends a few samples from time to time. And why not? My mistake is that I’ve always expected others to derive as much pleasure from doing (or returning) favours as I have.

I’m sure Judi Dench would have been very sad to know that half a dozen people were turned away that day – for no good reason whatsoever – because of some self-important official.

Slap!

Friday, 9 February 2007

Old and desolate

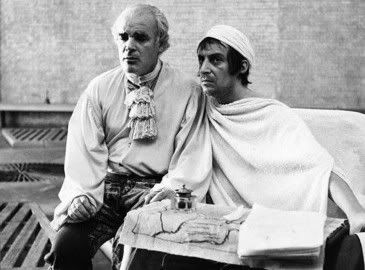

Patrick Magee as Sade and Ian Richardson as Marat

... that’s how you feel when the idols of your youth disappear. Gods should not be allowed to die.

The actor Ian Richardson died this morning, in his sleep.

I am in shock.

The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as performed by the inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade (at the time of its release in the ’60s, people joked, 'I haven't seen the film, but I've read the title') or Marat/Sade, directed by Peter Brook, changed the course of my life – literally. I owe my love of the theatre to that film and it's because of it (and more especially because of Ian Richardson, who played Marat) that I stopped studying psychology at the Sorbonne and took up English instead. The first time I saw it, I stayed for two performances and nearly missed a train I had to catch that evening.

I will write more later.

Update (10 February): By the time the world became aware of him, Ian Richardson was already past his prime. Yes, he was wonderful as Francis Urquhart in House of Cards. Absolutely wonderful, but...

I was there. I was there, night after night, matinee after matinee, in the dark and womblike auditorium of the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, standing at the back of the stalls, leaning on my railing, lapping it all up: the scenery, the costumes, the music, the verse, the emotions. I was there when Ian Richardson was a god and he knew it and he had the audience hanging on his every inflection, when his voice soared... ah!...

Don’t just take my word for it. Every review of every play he was in mentioned the voice, but this is what Roger Lewis says in his book Stage People:

He sings his sentences, his voice swooping from a bellow to a whisper, from a hoot to a silence. Richardson’s voice is his instrument; he is conscious of it and proud of it; he plays upon it and with it. He can draw out a single word into an alarming stutter of syllables, like a libretto fragmented and reproduced under the stave; he’ll then speed ahead, putting a girdle around a paragraph in four seconds.It was the voice above all. But also the poise, the stillness. And the wit. And the sense of danger too. There, on the stage, not preserved in aspic for posterity.

He’s gone and hardly anyone is mentioning Shakespeare. My 20-year-old self would never have believed it. It makes me very sad now.

I knew Ian Richardson – a tiny little bit. I lived in his Stratford house, with two other girls, for the best part of 1974. He wasn’t there; he was renting it out to us. The house was very cold; my room was the coldest of all, but I didn’t care. There was a throne from some past RSC production on the patio; Marat’s tin bath was rusting at the bottom of the garden; his acting editions of Penguin Shakespeare were sitting on the shelves in the living room (they got thrown away a little later and I now wish I had ‘stolen’ a couple of them, but I didn’t dare at the time). Fans used to walk past the house, stop and point at it. Told you he was a star.

He used to scare me to death, from time to time, by turning up unannounced (always accompanied by his wife, who usually remained silent) and demand to know why the lawn hadn’t been mown (the neighbours were always complaining). I’ve heard Marat and Francis Urquhart and Angelo and Richard II yell my name from the bottom of the stairs and then discuss mundane things. It was wonderful.

Later that year, when I was working at the Aldwych Theatre (dressing the tallest actor in the company, of course – some kind of hazing I believe it was), we used to pass each other backstage every night and exchange no more than a smile, except once, when he said something so bitchy about someone we both knew that I was in hysterics for the rest of the evening. That’s also how I want to remember him: rather camp and mercurial.

I visited eBay last night: lots of people are trying to cash in on Ian’s death and flogging photos and letters signed by him. I have a few of those, among them a very grumpy letter: I had reproached him for wasting his time on rubbishy stuff (it must have been before House of Cards), and he had written back defending his choices. I wasn’t convinced, and I was right: a few years later, he said in an interview that he bitterly regretted not doing stage work any longer, and Shakespeare in particular.

I also have the waistcoat he wore as the Government Inspector at the Old Vic (I didn’t steal it; I bought it for a few pounds at a charity auction). No, you won’t find it listed on eBay either – not now, not at any time in the future.

What else can I say? I saw him recently at the National Theatre, in a play, and also talking about his career (I went mainly because my younger self would not have missed it and I owed it to her). He was just as entertaining as ever. He said he would probably never act on the stage again (a premonition?) and his one regret was that he’d never got a chance to tackle King Lear. He sounded happy, though.

There’s no doubt about it: it was the voice that did it.

Update: To hear the voice that mesmerized me 40 years ago, click here

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)